Did A Drag Queen Start The Stonewall Riots?

Historians Say....MAYBE

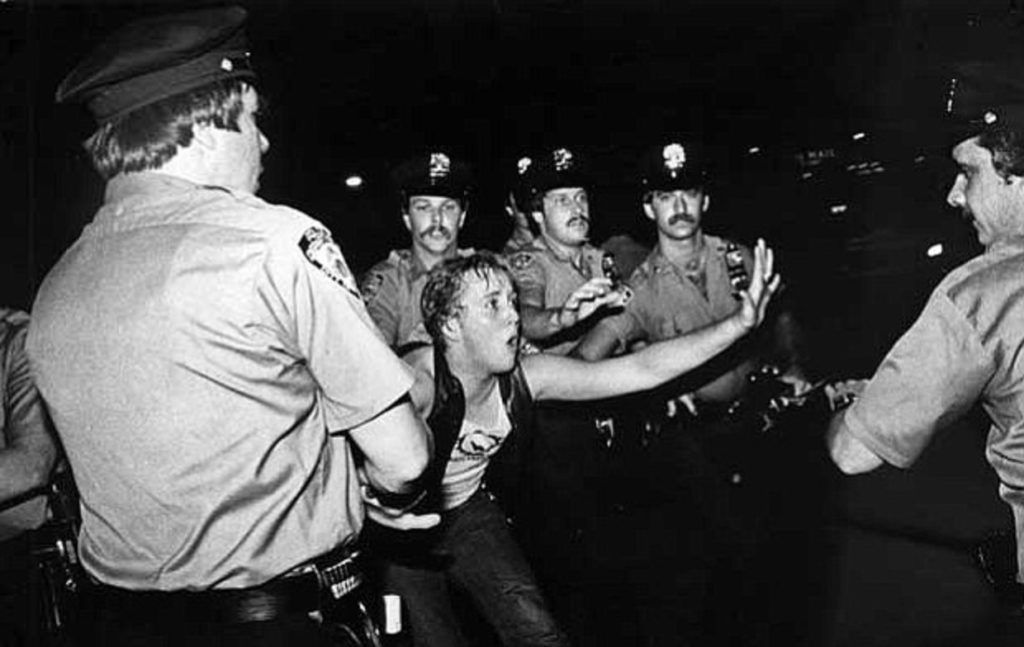

Picture this: It's June 28, 1969, and the Stonewall Inn, a bustling gay bar in New York City's Greenwich Village, is raided by police. The LGBTQ+ patrons have had enough of the harassment and discrimination, and they decide to take a stand.

A riot erupts, spanning several days and marking a turning point in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. But who exactly lit the spark that ignited this historical blaze?

Did a drag queen start the Stonewall Riots?

Let's dive into the heart of this controversial question.

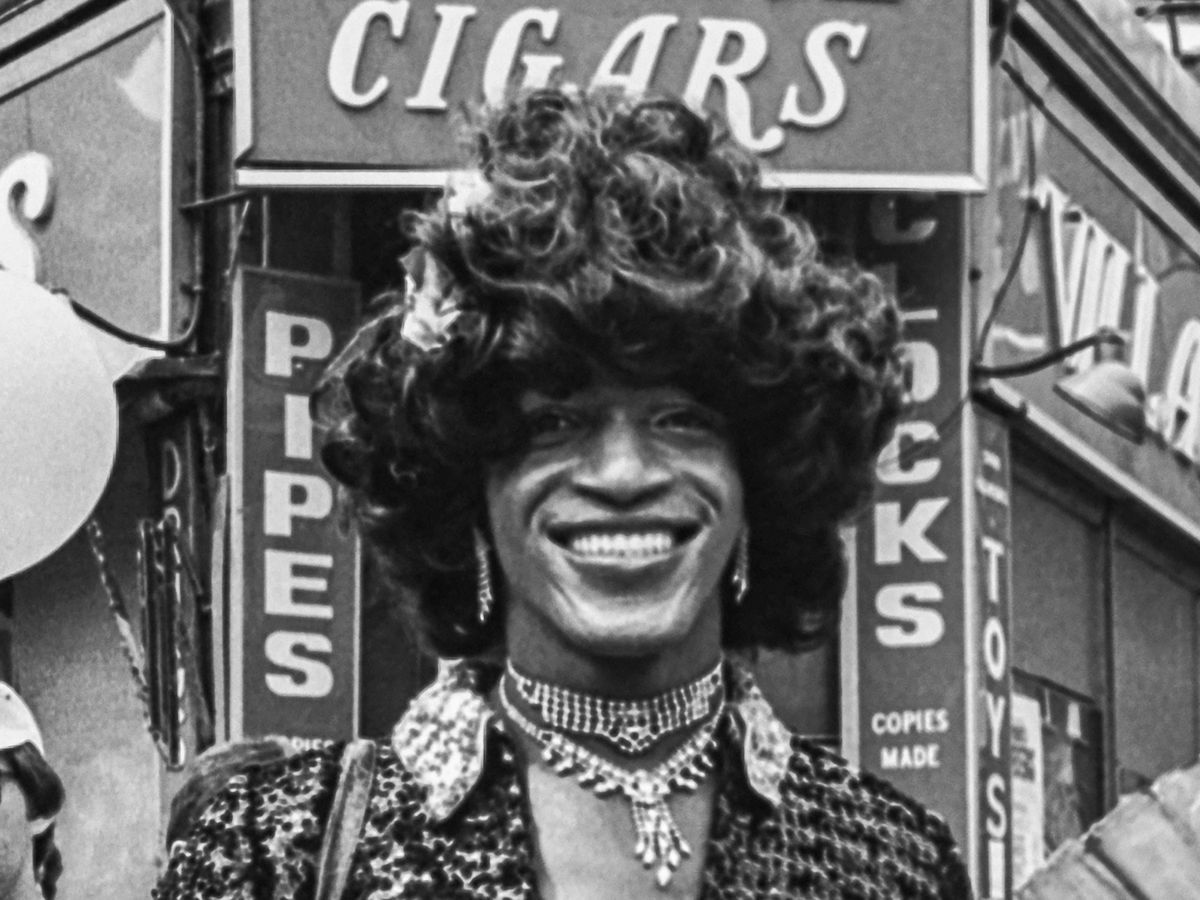

The Marsha P. Johnson Theory

Marsha P. Johnson, born Malcolm Michaels Jr., was an African American drag queen, sex worker, and transgender activist who played a significant role in the LGBTQ+ community during the 1960s and 1970s.

Johnson was known for her flamboyant personality, colorful wardrobe, and captivating performances, making her a popular figure in New York City's gay scene.

Her activism was not limited to the stage; she was also a founding member of the Gay Liberation Front and later co-founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) with fellow activist Sylvia Rivera, providing housing and support to homeless LGBTQ+ youth.

The Marsha P. Johnson theory posits that Johnson's actions during the raid on the Stonewall Inn triggered the riots. According to some accounts, Johnson threw a shot glass at a mirror in the bar, an event referred to as the "shot glass heard around the world." Historian David Carter quotes Johnson in his book "Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution": "I got my civil rights!" after throwing the shot glass (Carter, 2004).

This act of defiance is often seen as the catalyst that inspired others to stand up against the police.

Johnson's involvement in the riots is corroborated by multiple eyewitness accounts. For instance, Bob Kohler, an activist and Stonewall regular, recounted Johnson's presence at the forefront of the protests: "Marsha was there, standing on top of a lamppost, urging the crowd to keep fighting" (Kohler, 1994).

Another witness, Randy Wicker, described Johnson as "one of the key figures that night" (Wicker, 1995).

However, Johnson herself provided a conflicting account of her participation in the riots. In a 1987 interview with historian Eric Marcus, Johnson stated: "I didn't get there until about two o'clock [in the morning], because when I got downtown, the place was already on fire, and there was a raid already" (Marcus, 1987). This statement complicates the narrative surrounding her role as the initiator of the riots.

Despite these inconsistencies, the Marsha P. Johnson theory has gained traction among historians and activists alike, as it highlights the vital role that transgender women of color played in the early LGBTQ+ rights movement. By examining Johnson's life and activism, we gain a greater appreciation for the resilience and determination of individuals who fought against oppression and discrimination.

The strengths of the Marsha P. Johnson theory lie in the numerous eyewitness accounts and Johnson's status as a prominent figure in the LGBTQ+ community.

However, the weaknesses arise from the conflicting statements made by Johnson herself and the absence of definitive evidence to support the claim that she was the sole instigator of the riots.

Ultimately, the Marsha P. Johnson theory serves as a powerful reminder of the role that transgender women of color have played in LGBTQ+ history, even as the debate surrounding the origins of the Stonewall Riots continues to unfold.

The Sylvia Rivera Theory

Sylvia Rivera, born Ray Rivera Mendez, was a Puerto Rican and Venezuelan transgender activist who made a lasting impact on the LGBTQ+ rights movement.

Rivera, who grew up in difficult circumstances and experienced homelessness, was a sex worker and a prominent figure in the New York City drag scene. She co-founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) with Marsha P. Johnson, providing housing and support to homeless LGBTQ+ youth.

Rivera's connection to the Stonewall Riots has been a subject of much debate. Proponents of the Sylvia Rivera theory argue that she played a pivotal role in initiating the uprising.

Some accounts claim that Rivera threw the first Molotov cocktail at the police, while others attribute this act to another protester. In a 2001 interview, Rivera clarified her involvement, stating, "I have been given the credit for throwing the first Molotov cocktail by many historians, but I always like to correct it. I threw the second one. I did not throw the first one!" (Rosenberg, 2001).

However, historian David Carter maintains that there is no evidence of Molotov cocktails being used during the first night of the riots (Carter, 2004).

Additionally, Rivera's presence at the beginning of the uprising has been questioned, as she was only 17 years old at the time and living on the streets.

In a 1998 interview, Rivera recalled being at a nearby park when the riots began: "I didn't get to Stonewall until about 2 a.m. Marsha and I were walking towards the bar when we saw people running" (Rivera, 1998).

Despite these discrepancies, the Sylvia Rivera theory highlights the role that transgender activists, particularly transgender women of color, played in the early LGBTQ+ rights movement. Rivera continued her advocacy work long after the Stonewall Riots, becoming an influential voice for transgender rights and fighting against the exclusion of transgender people from the mainstream gay rights movement. In a 2000 speech, Rivera passionately declared, "We have to be visible. We should not be ashamed of who we are" (Rivera, 2000).

The strengths of the Sylvia Rivera theory lie in the multiple accounts that place her at the scene of the riots, her activism in the LGBTQ+ community, and the powerful symbolism of a transgender woman of color standing up against oppression.

However, the weaknesses arise from conflicting accounts of her presence during the early hours of the uprising, the absence of definitive evidence linking her to the first Molotov cocktail, and the contradictions in her own statements.

In conclusion, the Sylvia Rivera theory contributes to the ongoing discussion surrounding the origins of the Stonewall Riots by emphasizing the important role that transgender activists played in the early days of the LGBTQ+ rights movement.

While the debate about Rivera's exact role in the uprising may continue, her lasting impact as a trailblazer for transgender rights remains unquestionable.

The Stormé DeLarverie Theory

Stormé DeLarverie was an African American lesbian, singer, and drag king whose life and activism left a lasting impression on the LGBTQ+ community.

DeLarverie was known for her groundbreaking work as the master of ceremonies and sole male impersonator in the Jewel Box Revue, a popular drag show that toured the United States during the 1950s and 1960s.

DeLarverie's unique stage presence and androgynous style challenged gender norms and paved the way for future generations of genderqueer and transgender performers.

Proponents of the Stormé DeLarverie theory argue that she played a crucial role in sparking the Stonewall Riots. According to some eyewitness accounts, DeLarverie was arrested during the police raid on the Stonewall Inn and fought back against the officers as they tried to restrain her.

The iconic moment that allegedly ignited the riots occurred when DeLarverie, after being hit on the head with a billy club, shouted to the onlookers, "Why don't you guys do something?" (Duberman, 1993).

DeLarverie's resistance against the police is supported by several eyewitness accounts. Jerry Hoose, a Stonewall regular, recalled her defiance in a 2008 interview: "She just looked like she was mad as hell, and she wasn't going to take it anymore" (Hoose, 2008). Another witness, Danny Garvin, described DeLarverie as "the Rosa Parks of the gay community" (Garvin, 2007).

However, DeLarverie's role in sparking the riots has also been challenged by conflicting accounts and a lack of concrete evidence.

Historian David Carter notes that there is no definitive proof to confirm that DeLarverie was the "butch lesbian" arrested during the raid, and some witnesses recall the woman in question as being white, not African American (Carter, 2004).

Nonetheless, the Stormé DeLarverie theory emphasizes the importance of recognizing the contributions of butch lesbians and gender nonconforming individuals in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights.

DeLarverie continued her activism after the Stonewall Riots, working as a bouncer at various lesbian bars in New York City and patrolling the streets to protect LGBTQ+ individuals from harassment and violence.

The strengths of the Stormé DeLarverie theory lie in the numerous eyewitness accounts that attest to her presence and resistance during the raid, as well as her trailblazing work as a performer and activist. However, the weaknesses stem from the conflicting accounts of her identity and the lack of definitive evidence connecting her to the inciting incident of the riots.

In conclusion, the Stormé DeLarverie theory adds another layer of complexity to the ongoing debate surrounding the origins of the Stonewall Riots by highlighting the vital role that butch lesbians and gender nonconforming individuals played in the early days of the LGBTQ+ rights movement.

While the exact details of DeLarverie's involvement in the riots may never be fully known, her courage and resilience as a pioneering activist continue to inspire future generations.

Alternative Theories and Perspectives

While the Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and Stormé DeLarverie theories are the most widely recognized explanations for the catalyst of the Stonewall Riots, other alternative theories and perspectives offer additional insights into the complex event.

By examining these alternative narratives, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse forces and individuals that contributed to the riots.

I. The Role of Street Youth

One alternative perspective places the street youth, many of whom were homeless or runaway LGBTQ+ individuals, at the center of the Stonewall Riots.

Historian and activist John O'Brien argues that these young people, who faced constant harassment and discrimination from both society and law enforcement, played a pivotal role in the uprising. In a 1995 interview, O'Brien claimed, "It was the street kids, the hustlers, and the most marginalized who really started the riots" (O'Brien, 1995).

This viewpoint is supported by accounts of the involvement of the street youth in the early stages of the riots. For example, eyewitness Lucian Truscott IV described the street kids as "the vanguard of the Stonewall Riots," noting that they were the first to confront the police and resist arrest (Truscott, 1969).

II. The Influence of the Black Cat and Compton's Cafeteria Riots

Another alternative theory considers the impact of previous LGBTQ+ uprisings on the Stonewall Riots. The Black Cat Riot in Los Angeles (1967) and the Compton's Cafeteria Riot in San Francisco (1966) both involved confrontations between LGBTQ+ individuals and police, and these events may have inspired the patrons of the Stonewall Inn to stand up against the raid.

Historian Lillian Faderman highlights the influence of these earlier events, stating, "Stonewall was not the first time LGBTQ+ people fought back against oppression, but it was a turning point because it was the first time such resistance was widely publicized and sparked a national movement" (Faderman, 2015).

III. The Power of Collective Action

Some historians argue that focusing on a single individual as the instigator of the Stonewall Riots detracts from the power of collective action. Rather than seeking a "hero" or "heroine" to credit for the riots, these historians emphasize the importance of the broader LGBTQ+ community's involvement.

In a 2009 interview, historian Ann Bannon cautioned against oversimplifying the narrative of the Stonewall Riots: "I think it's important not to assign the entire credit or blame to one person. Stonewall was a spontaneous uprising of an entire community that had been pushed too far" (Bannon, 2009).

Furthermore, activist Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, a transgender woman who was present during the riots, emphasized the collective nature of the uprising in a 2015 interview: "It wasn't a few people doing something, it was everyone. We were all in it together, fighting for our lives" (Griffin-Gracy, 2015).

The strengths of these alternative theories and perspectives lie in their ability to encompass the diverse range of participants and influences that contributed to the Stonewall Riots.

By considering these narratives, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of the event and its significance in LGBTQ+ history. However, the weaknesses of these alternative theories stem from the lack of definitive evidence and the inherent difficulties in reconstructing a complex, multifaceted event.

In conclusion, exploring alternative theories and perspectives allows us to appreciate the intricate tapestry of forces, individuals, and events that culminated in the Stonewall Riots.

As we delve deeper into these narratives, we can better understand the collective power of a marginalized community that rose up against injustice and sparked a transformative movement for LGBTQ+ rights.

While the debate over who or what specifically triggered the Stonewall Riots may never be resolved, the legacy of this watershed moment in LGBTQ+ history remains undeniable, as does the importance of recognizing the contributions of countless individuals who fought for their rights and dignity.